– The hunting pressure on wolves in Karelia has grown as part of the efforts to regulate the carnivore’s numbers. Hunters are paid a bounty for each animal they kill and get a moose hunting license. Lately, due to sampling arrangements introduced by the Karelian Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, the laboratory has been receiving biological material from almost all wolves taken down in Karelia. If a wolf’s exterior is somewhat different from what is normal for the species, the sample is supplied with a relevant comment. In 2021, we received a sample marked with a single word – “hybrid”. A test with a mitochondrial DNA polymorphism marker confirmed the individual was of a mixed origin, the breeders being a female dog and a male wolf, which is extremely rare in the wild as it is usually vice versa – said Anastasiia Kuznetsova, Junior Researcher of the Institute of Biology KarRC RAS.

Junior Research of the Institute of Biology KarRC RAS Anastasiia Kuznetsova at work in the lab

This was the first wolf-dog hybrid detected by Karelian scientists. It is, indeed, more than just a curious finding: hybridization with dogs is one of the consequences of human interference into the wolves’ population structure. At times of intensive extirpation, breeding partners for wolves are in deficit. Meanwhile, wolf hunting in Karelia has been growing since 2016. The Karelian population totals around 400 animals. Before 2010, hunters officially took down some 100 wolves a year. In 2016, as the bounty was doubled and wolf hunters were additionally allocated moose hunting licenses as a bonus, withdrawals grew to above 160 animals, peaking in 2018, when 236 wolves were killed. Nonetheless, wolf numbers in Karelia have remained at about the same level, most likely due to arrivals from neighboring regions.

Hybridization, coupled with a loss of genetic diversity caused by inbreeding, may jeopardize the population in general – the animals’ viability is affected by a loss of useful qualities and accumulation of ‘bad’ mutations. Also, the behavior of wolf-dog hybrids is less predictable than in pure wolves and is therefore more dangerous for humans.

In the attempt to find out how common interspecies hybridization is in the Karelian wolf population by means of molecular genetic analysis, zoologists implemented a project funded by the Russian Science Foundation. The project leader was Head of the laboratory Konstantin Tirronen.

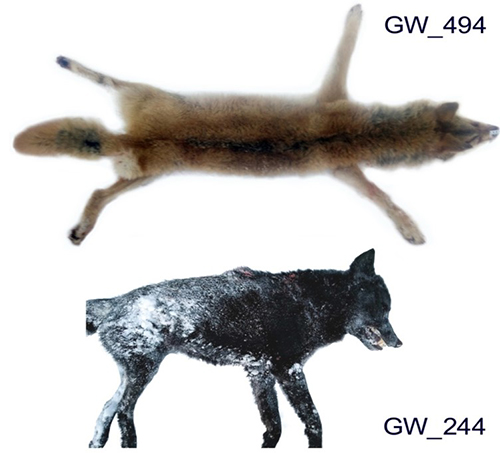

Within this project, scientists processed samples from 90 individuals, one of which proved to be a feral dog. Four of the animals had exterior traits suggesting they were hybrids: in addition to the animal mentioned above, one wolf was full black, which is atypical of the animals on our continent. Black wolves do live in North America, but there, too, this coat color is a result of hybridization with dog many generations ago. Black wolves in Europe are an utter rarity. According to Finnish scientists, a pack of this color type has actually been noted not far from the border with Russia, near the Lahdenpohja District of Karelia, which is where the mysterious sample comes from. Another wolf was red-colored and resembling an akita inu dog; and one more sample was accompanied by the comment “White paw pads and white claws” – also suggesting the animal could be of mixed origin.

Top: red-colored hide of a presumed wolf-dog hybrid GW_494, genetically identified as a “pure” wolf; bottom: black wolf-dog hybrid GW_244. Photo from Polar Biology (provided by hunting authorities)

Samples were investigated by mitochondrial DNA polymorphism analysis and microsatellite analysis. To explore hybridization, genetic material from a random wolf sample had to be analyzed together with samples from dogs with specific exterior features.

– It was necessary to make the genetic profiles of wolves and dogs – large and medium-size mongrels, i.e. those potentially capable of breeding with wolves. We contacted an animal shelter in Petrozavodsk for help. Its staff responded promptly and provided us with hair from 12 dogs. We did the profiling and performed the genetic analysis, – relayed Anastasiia Kuznetsova.

Three of the four wolves that hunters were uncertain about were indeed hybrids. Surprisingly for the researchers, the red animal proved to be a wolf. This result was triple-checked. And yet, scientists still doubt its pedigree, since the animals’ morphological traits clearly point to a mixed origin. It is likely that the hybridization happened several generations ago, while the methods used in this study can trace the event only 2 or 3 generations back.

The results of the study were published in the Polar Biology Journal. The findings confirm the hypothesis that wolves use interspecies hybridization and inbreeding as a behavioral adaptation for the species survival under highly adverse conditions, including pressure from humans.

– Wolves play a crucial role in the nature: they regulate ungulate numbers, kill sick and weak animals. Exterminating wolves, we shatter the balance in the ecosystem. There are cases from European countries, where wolves were totally exterminated in the past, but after the environmental legislation was revised, many of the population recovered. That said, wolf hunting has a long history and humans have become a regulating factor for the species. However, a firm and clear-cut wolf management policy is still missing. We’re already seeing consequences of the growing hunting pressure. Adequate measures are to be worked out, and scientists must be involved in the process, – the expert believes.

Wolves’ raids of human communities are provoked by hunger and harsh winter conditions. One of the factors here is landfills or waste dumps, where wolves can find food – leftovers and stray dogs. Another target for the gray predators is dogs walking the streets unattended or kept outside of enclosures. Scientists urge people to remember about the safety measures: keep pets inside the house on winter nights and carry things to deter wolves when going into the woods.

Anastasiia Kuznetsova on a field trip

In February, Anastasiia Kuznetsova won a contest of academic articles published in 2024 among Natural Sciences papers. The main research focus is the brown bear and its genetic structure. Studying for the master’s degree at the Petrozavodsk State University, she was a student of Dr. Pyotr Danilov, who suggested that she engages in genetic studies – a relatively new line in science. While taking the doctoral course at KarRC RAS, Anastasiia spent some time as a laboratory intern in Estonia, Finland and Norway, and then proceeded with her career at the Institute of Biology.